- Undergraduate

- Foreign Study Program

- News & Events

- People

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

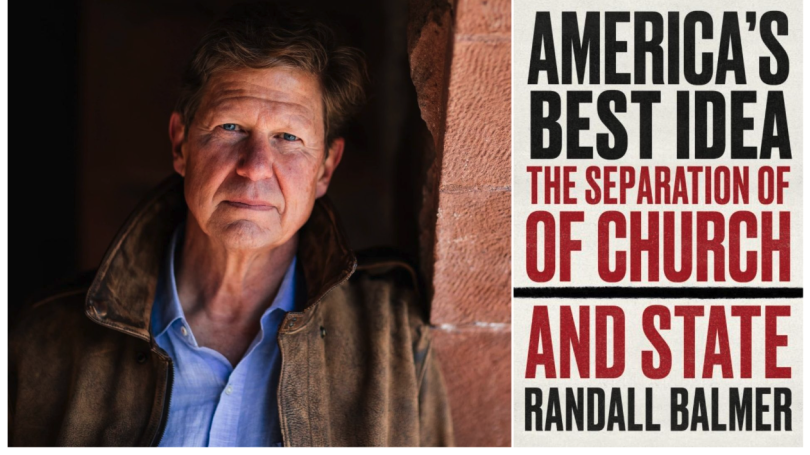

As an ordained Episcopal priest, Randall Balmer has a unique take on the separation of church and state in America.

"I think it's America's best idea," says Balmer, the John Phillips Chair in Religion and prize-winning author of more than a dozen books. "I'm not making this argument as a secularist; I consider myself a person of faith. It's been spectacularly successful. But I think it's under attack today as in perhaps no time in American history."

In his forthcoming book, America's Best Idea: The Separation of Church and State, due out in August, Balmer argues that the historical division between religion and government in the United States is being eroded—with potentially disastrous consequences.

In the following Q&A, he explores the origins of the First Amendment, the expanding role of religion in publicly funded activities, and the potentially "catastrophic" consequences of a blurred line between church and state.

The First Amendment was a groundbreaking concept in its time. Why do you think it was passed?

The idea of trying to construct a government without the interlocking support of religion was unheard of in Western culture. I think the founders were motivated by several things. First, they were well aware of the chaos and violence that had attended these various contestations over church and state in Europe, certainly in England, and they wanted to avoid that. But the other thing is that if you look at the composition of the American colonies on the eve of setting up a new government for the United States, you had an extraordinary diversity of religions—from Jews in New York to Huguenots, Presbyterians, and the list goes on.

I think the founders realized that the idea of anointing one religion as the favored or established religion for this new nation simply was not going to work. So they decided, both to accommodate religious diversity and also to shield the new government from religious factionalism, that the separation of church and state was the way to go about it.

What has been the result, historically, of this separation?

It's been a resounding success. It has shielded the government from religious factionalism, but it has also set up what I like to refer to as a "free marketplace" for religion in America, so that you have all these different religious groups competing with one another for popular followings. That has lent an energy, dynamism, and vitality to religion in America that I think is unmatched anywhere in the world.

Can you offer an example of how the First Amendment has yielded a positive result?

Probably the best example has to do with the funding for religious education going back into the 19th century. Many of the states adopted what they call Blaine Amendments: legislation that would prohibit the use of taxpayer money for religious education. That allowed public education to flourish in the 19th century and well into the 20th century.

Public school is the one place where students from various socioeconomic backgrounds, religions, races, and ethnic backgrounds can come together and explore their similarities as well as their differences in the classroom and on the playground. And to me, that sounds like a recipe for democracy. That would be the best example of how the First Amendment and the separation of church and state worked to everyone's advantage.

Now, I'm perfectly willing to acknowledge that what I've just described is an idealistic vision, and it's not always lived up to that. But I think if we have any hope whatsoever of maintaining this precious democracy that was hard won by the founding fathers and subsequent generations, we have to safeguard public education.

One might also make the case that if America wishes to remain an economic superpower, it needs as many residents as possible educated and working.

Absolutely. Consider that this July marks the centennial of the Scopes trial in Dayton, Tenn., in which high school teacher John Scopes was tried for violating the Butler Act, a state law prohibiting the teaching of evolution in public schools. Many other states had anti-evolution laws on their books, too. The United States was dreadfully behind on science education up until the 1960s because of these laws that essentially imposed someone's religious orthodoxy on public education. It wasn't until Sputnik and, in particular, John F. Kennedy's vision for a man on the moon by the end of the 1960s, that the United States began catching up on science education after all those decades.

In your book, you argue that "America's best idea" is under threat. Can you elaborate on that?

I like to say that I wish the Supreme Court had half as much deference to the First Amendment as it does to the Second Amendment. The Supreme Court has been steadily whittling away at this wall of separation between church and state. And to me that's catastrophic. It certainly is undermining public education. It used to be that the prohibition against using taxpayer money for religious schools was the bright line in this separation between church and state. And now that has been virtually obliterated by the various decisions by the Supreme Court, including the Montana ruling [which found it unconstitutional to bar state funds from religious schools in a scholarship program], and the Kennedy case [which allowed coach Joseph Kennedy to pray on the football field]. The prayer on the football field was, in many ways, the harbinger of further attacks on this wall of separation between church and state.

Why do you think this "whittling away" is happening?

I think there's a segment of the American population that sees itself as under attack. It sees their values under siege in what they regard as an increasingly secularist society. And I think part of the problem is that they have enjoyed a kind of hegemonic hold on American society going back centuries in American history, and all of a sudden the perception is that they are a minority. But if you look at voting patterns and voting outcomes over the last 40 years or so, this is the group that is really setting the political agenda. Nevertheless, there's a strong rhetoric of victimization within the white evangelical community in particular.

I would say it was the signing of the Hart Celler Act, officially known as the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, that removed quotas and really set the stage for true multiculturalism in American society, that began to change things. Thereafter, as more and more folks started coming to the United States, many of whom did not share Christian convictions and had other religious sensibilities, white evangelicals began to feel their hold on American society lessen. And they've been trying to fight back ever since.

What most concerns you about this blurring between church and state?

My greatest fear is that public education is going to be destroyed by the authorization of taxpayer money to pay for religious education. Subsidies are not enough to cover full tuition at private schools, in most cases. So it's only the relatively affluent families who can afford to send their children to these schools, and they're being subsidized to do that. And that means, typically and tragically, students from less privileged households who don't have the economic or the educational advantages that these other students have are going to be crowded into increasingly substandard public schools.

There's a real cynical process at work here. I spent my high school years in Iowa. The Iowa Public Education system was one of the crown jewels in the whole nation. What has happened since is that state and local governments have steadily diverted funding from public schools. Then they circle back five, six, eight years later and say, "Look, our schools are failing. We have to subsidize students' education in private or religious schools." The end result is the vacating of public education. And that worries me. I think it undermines the pillars of democracy.

The separation of church and state has worked remarkably well throughout American history, and it has served the purposes of both secularists and religious people. Why would we want to compromise it at this point?